Deep in the heart of Lincolnshire, octogenarian Tom Waterfield spends his days climbing up and down narrow, well-trodden ladders inside one of the last functioning windmills in the world.

His knitted wool sweater covered in a fine dusting of flour, he pushes his glasses back onto his nose and holds up a handful of spelt grains. His face lights up as he describes how he grinds these ancient Roman grains into flour between millstones – the traditional way.

‘Everything we make is organic. Because what is the point otherwise?’

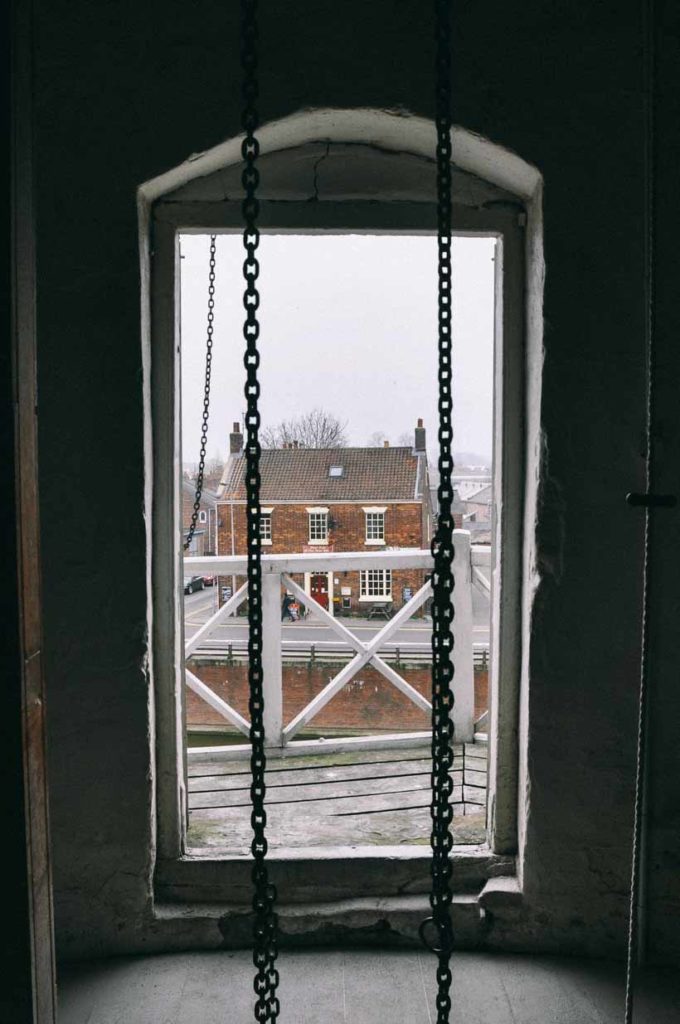

Tom Waterfield and his sons purchased and restored the Maud Foster Mill in 1987, and ever since then have been operating one of the finest examples of a Lincolnshire windmill (and the tallest in the country).

We trundle up the narrow, steep stairs hugging the inner walls of the windmill. Tom explains what each of the floors held and what all the machinery does. We reached the grinding floor (known as the stone floor, as this is where the grinding stones reside and do their work), and he started to empty bags of grains into the top of each hopper – the bin that holds the grain. From there it goes down into the ‘feed shoe’, which shakes the grain out into the eye of the millstones, grinding the grains between the stones.

It emerges around the edges as flour, goes down a spout and into a sack on the next floor.

I asked about the darkness of the flour that was feeding through from the stone floor above. Tom took me to the grains and grabbed a handful: ‘it’s spelt. That’s what gives it that darker colour. It’s an ancient grain, medieval.’

Known by many to be the finest examples, Lincolnshire windmills are identifiable by their onion-shaped cap on top, and many have more sails than other styles of windmill. Tom started telling us about the sails: at 37 feet, they are the longest working sails on a windmill in the UK.

Inscribed in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity since 2017, the art of operating a windmill is a practice that has been around since the 1200s. In the Netherlands, there are a declining number of people earning their livelihood from the craft. There are currently approximately forty professional millers left; together with volunteers, they keep the miller’s craft alive.

Artisanal flour making is a dying art. But like any specialty food, artisan bread is only as good as the sum of its parts. Without quality flour, our urban specialty bakers are left without a canvas for their paint.

How can we help preserve stoneground milled flour? Easy – support our millers by buying from them – direct, if you can.